|

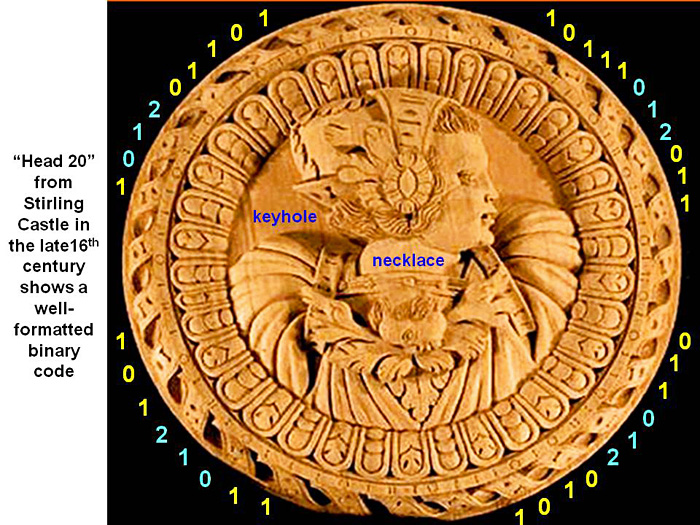

A human-made binary code just as amazing as those seen in crop pictures: did King James I and Francis Bacon leave us a coded text message about Mary Queen of Scots in Stirling Castle “Head 20”? Usually on this website we only try to solve crop-circle puzzles or codes, which are sometimes formatted in binary (see for example time2007n or /Poirino2011). Yet occasionally another interesting human-made code comes along, which practically begs to be solved! Several weeks ago, I noticed that the facial image of a young woman, which was carved onto Stirling Castle “Head 20” during the late 16th or early 17th century, shows both a “keyhole” image and a well-formatted “binary code”. One can easily see where a small “keyhole” image was carved along the rear of that woman’s headscarf:

Likewise along the outer perimeter, we can see many small symbols of the kind “0, I or II” as for a modern binary code. Two large symbols “I” or “II” in the upper part of her headscarf also suggest a binary code. All of those symbols were rediscovered by an expert woodcutter, John Donaldson, while he was carving new and exact replicas of the Stirling Heads (see stirlingheads exhibition). They give us a strong indication that the wooden carved image contains some sort of hidden cipher or code. Yet when was that code carved, who designed or carved it, and what does it say exactly? Francis Bacon did not invent the modern binary code until 1576, and did not publish it widely until 1623 By the early 17th century, alphabetic ciphers such as those invented by Francis Bacon were known as “key alphabets”, thereby explaining the “keyhole” symbolism within Stirling “Head 20” (see exploratorium). When did such arcane knowledge first become widely known? Bacon devised his new binary code while living in Paris from 1576 to 1579, but did not publish it formally in a scientific journal until 1623 (see key to biliteral to lougrich). Thus the Stirling “Head 20” code could hardly have been designed and carved until 1580, or more likely from 1600 to 1620, when Francis Bacon was a close friend of King James I who owned Stirling Castle. Who designed and carved the code? Mary Queen of Scots lived in Stirling Castle as a child from 1543 to 1548, and then again as a young woman from 1562 to 1566. She used coded messages quite regularly for political purposes, just as the leaders of governments today send coded diplomatic cables (see Babington_Plot). Yet she was imprisoned in 1568, and executed for “treason” in 1587. Mary could not have commissioned “Head 20” at Stirling Castle, because the modern binary code was not invented and made widely known, until long after she was languishing in prison. “Head 20” could have been commissioned however by her son James I, who later became the king of both Scotland and England. He grew up as a child in Stirling Castle, and his first child was born there (see James_I_of_England). After leaving for England to become king in 1603, he visited Stirling Castle again for six months in 1617, before passing away in 1625. Francis Bacon was a close associate of King James I from 1607 to 1621 From 1607 onward, Francis Bacon acted as Solicitor General to the Crown. In 1609 there is speculation that he may have performed a final edit to the King James Bible (see www.sirbacon.org). By 1621 he fell to charges of bribery, because a faction in Parliament disliked his close friendship with James (see Francis Bacon). Surely Bacon’s work on binary codes would have been known to him? “During the reign of King James I, Francis became a principal adviser to the crown in all matters. In March of 1617, James even appointed Francis to act as a virtual regent in England, while he departed to Scotland for six months” (see www.fbrt.org.uk). When would have been a better time for James to commission an oak carving of his mother Mary, as shown in Stirling Castle “Head 20”, than in 1617 with some help from his friend Francis Bacon? The carved image within “Head 20” may be that of James’s mother Mary as a child or young woman After her tragic execution in 1587, did King James I of England quietly commission a portrait of his mother Mary Queen of Scots, as a child or young woman? It could then be displayed with similar oak carvings of her father James V and mother Marie of Guise, already hanging in the same room at Stirling Castle. The first wife of James V was shown there, plus his uncle and father (see what-stirling-heads-show or www.youtube.com). Stirling “Head 20” shows a young woman of similar appearance to Mary Queen of Scots at age 6 to 12, wearing apparently the same beaded necklace as worn in one of her portraits from 1555:

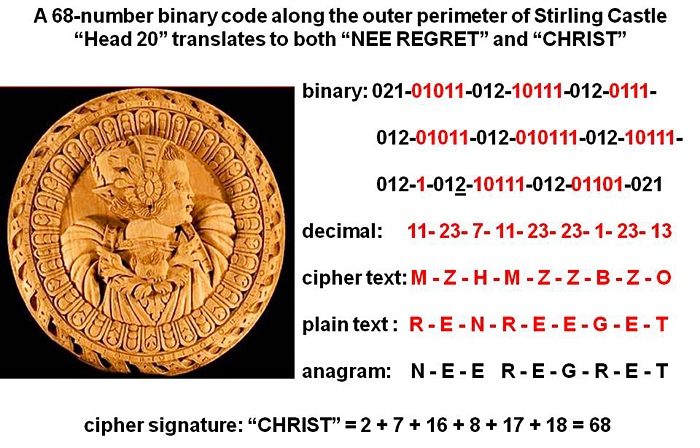

Why would James have commissioned an oak carving of his mother in the early 17th century, long after she had died, while he was the powerful king of both Scotland and England? “Most near-contemporary paintings of Mary date from after her death during the reign of James I, when her status as the mother of a legitimate monarch lent her credibility. During her lifetime she was wildly controversial” (see arts.monarchy). Here I will try to explore any brief text messages that may be coded subtly in that medieval oak carving, which could have been lost to us for the past 400 years. Binary codes and alphabets in the late 16th or early 17th century During the late 16th or early 17thcenturies, most people used a 24-letter Elizabethan alphabet in which the letters I = J and U = V were interchangeable, rather than our modern 26-letter alphabet. A detailed analysis of Stirling “Head 20” now suggests that its artist may have designed a simple alphabetic cipher, using that 24-letter alphabet, to accompany Mary’s carved portrait in wood. The decoded message seems to show a transpositional or Caesar shift of +5 letters relative to A = 0 or Z = 23, again as used commonly in diplomatic messages of the time. Sixty-eight binary numbers from the outer perimeter of “Head 20” may be transcribed as follows: 021-01011-012-10111-012-0111- 012-01011-012-010111-012-10111- 012-1-012-10111-012-01101-021 Here 012 or 021 are formatting marks. The first 012 marks any general space between adjacent five-digit binary numbers (mostly), while the second 021 marks “start” or “end” in a circular sense. One underlined formatting mark 012 denotes a “crushed petal” from the inner border of that wood carving. It was placed carefully to suggest that the binary code was “compressed” nearby at a single binary number “1”. All of the other binary numbers translate clockwise into decimal as 11 - 23 - 7 - 11 - 23 - 23 - 1 - 23 - 13. They presumably provide nine coded letters from a 24-letter Elizabethan alphabet, ranging from A = 0 = 00000 to Z = 23 = 10111. One could not read this code in a counter-clockwise sense, because then all of the formatting marks would be reversed as 210, while some of the binary numbers would increase to 11101 = 29. Elizabethan alphabet of 24 letters where A = 0 = 00000 or Z = 23 = 10111

We can plausibly decode this message using the relative frequencies of single letters E T O A N I R S H D L C W U M F YG P B V K X Q J Z or double letters SS EE TT FF LL MM OO in the English language. Such frequencies were also known to code-breakers in the 16th or 17th centuries, because they used similar ciphers for diplomatic communications. Assigning certain English letters to different parts of the code Let us first try to identify the binary number 23 = 10111 = BABBB which occurs four times in our message: Caesar shift +5 letters from 23 = “Z” to 4 = “E” 11 - E - 7 - 11 - E - E - 1 - E - 13 Next let us try to identify the binary number 11 = 01011 = ABABB which occurs twice: Caesar shift +5 letters from 11 = “M” to 16 = “R” R - E - 7 - R - E - E - 1 - E - 13 Now let us try to identify three binary numbers which occur only once: 13 = 01101 = ABBAB Caesar shift +5 letters from 13 = “O” to 18 = “T” R - E - 7 - R - E - E - 1 - E - T 7 = (0)0111 = (A)ABBB Caesar shift +5 letters from 7 = “H” to 12 = “N” R - E - N - R - E - E - 1 - E - T 1 = (0000)1 = (AAAA)B Caesar shift +5 letters from 1 = “B” to 6 = “G” R - E - N - R - E - E - G - E - T Nine English letters seem to provide an anagram for Mary’s life We can rearrange those nine letters fairly easily to find: N - E - E - R - E - G - R - E - T or N - E - R - E - G - R - E - T - E If this scheme is correct, then nine coded letters from Stirling “Head 20” may provide a simple anagram for the phrase “NEE REGRET” in Scots or “NE REGRETE” in French. The first word “nee” or “ne” would be written as “no” in modern English, “nae” in Scots, “ne” in French, or “nee” in Old English, Dutch or German. A local historian has confirmed that "nee" would mean “no” in lowlands Scottish at the time of James’s rule (J. Gibsone, personal communication). Mary lived in France for many years, and inscribed on her clothes a French phrase “En ma Fin gît mon Commencement” or “In my End is my Beginning” while imprisoned in England. She loved ciphers or codes. It would have been a good way for her son James to honour and remember her, while not drawing upon himself the anger of the English people with whom she was still deeply unpopular. Sixty-eight binary numbers may signify a year 1568, when Mary was first put on trial Sixty-eight binary numbers were provided in total, although some could have been made shorter (010111) or others longer (1), to match an expected five binary numbers per English letter. Could this be because the artist wished to note a year 1568 in which Mary escaped from prison at Loch Leven, and was first tried at the Conference of York for her “Casket Letters”? The length of characters in that code varies as 5-5-4-5-6-5-1-5-5, and would have totalled 9 x (3 + 5) = 72 without an abbreviation of (00001) to (1). Ten French letters as “NE REGRETTE” would give 10 x (3 + 5) = 30 + 50 = 80, while eight English letters as “NO REGRET” would give 8 x (3 + 5) = 64. In order to reach 68, the designer of that code had to start from a 72-number, nine-letter message, then shorten or compress one character from (00001) to (1) where four extra zeros were superfluous. This interpretation seems consistent with the number of “petals” found along its inner border, since 36 petals would match 2 x 36 = 72 binary numbers in the original code. One petal was actually “crushed” to suggest a numerical compression from (00001) to (1), or from 72 to 68 in total, just like we do today for modern JPG files. It remains unclear why the artist changed two other characters to lengths of “4” or “6” from “5” and “5”. Sixty-eight binary numbers may also signify the word “CHRIST” The number “67” was used commonly by Francis Bacon to secretly sign his work, whether by simple forward or reverse alphabetic ciphers (see bacon_&_the_tempest or essay-ciphers). We therefore searched for some word or phrase that might add up to “68” in either of those ciphers, using binary-number assignments as shown above? So far our only plausible match is to the word “CHRIST” = 2 + 7 + 16 + 8 + 17 + 18 = 68. Mary’s last words before her execution were: “I believe firmly to be saved by the passion and blood of Jesus Christ, in whom I believe according to the faith of the ancient Catholic Church of Rome, and so I shed my blood” (see eyewitness 2). A complete summary of all coded messages within Stirling Castle “Head 20” is shown below:

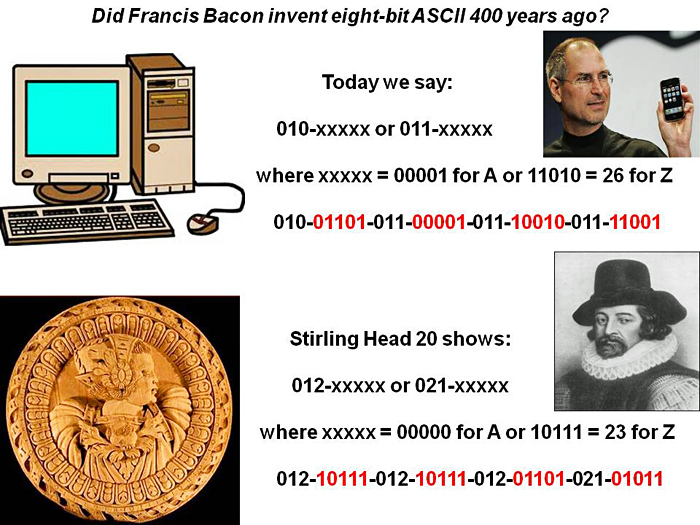

Interestingly, each of those 36 petals from the inner border of “Head 20” shows three marks or divisions, thereby yielding 3 x 36 = 108 parts in total, which was a cipher for “Francis” (see essay-ciphers). Stirling “Head 20” shows the world’s first eight-bit binary code What seems truly remarkable is that Stirling “Head 20” definitely shows the world’s first eight-bit binary code, just as we use in modern computers. The eight-bit binary code was not invented again until a development of seven-bit ASCII during the 1960’s, and its subsequent conversion to eight-bit ASCII for today’s computers. Today we write 010-xxxxx or 011-xxxxx to specify the complete English alphabet in eight-bit ASCII code, where xxxxx = 00001 for A, or xxxxx = 11010 = 26 for Z. That Stirling code shows almost the same features as 012-xxxxx where xxxxx = 00000 for A, or xxxxx = 10111 = 23 for Z:

Thus Francis Bacon seems to have invented the basic principles of ASCII code 400 years ago! There was likewise a German monk who found the “Mandelbrot set” 700 years ago (see mandelmonk). Naturally I would be interested if other readers might come up with another plausible scheme of decoding for “Head 20”, which could tell us something else different and/or informative? Mary’s failure at coding schemes was what ultimately did her in! To conclude, King James I may have reminded us, four hundred years after his mother’s death, that Mary Queen of Scots led a colourful and tumultuous life, with “no regret” and a faith in “Christ”. Her greatest error was perhaps to send out coded messages from her prison cell, in an attempt to assassinate Queen Elizabeth of England. Unfortunately Mary’s coding schemes were quite “weak”, and easily broken by Elizabeth’s agents such as Thomas Phelippes who were experts at coding (see spies). Her son James however, helped possibly by his friend Francis Bacon, seems to have concocted a much more long-lasting code which was not noticed and/or broken for the past 400 years. Red Collie (Dr. Horace R. Drew) P.S. If this historical code interests you, and you wish to learn more about “crop circle codes” which are equally or more interesting, then please see some of the recent articles on Crop Circle Connector Research (cropcircleresearch) such as time2011n or time2011m. Appendix 1. A long history of ciphers or codes in medieval churches or spy agencies Even prior to the work of Francis Bacon, there was a long history of ciphers or codes in English medieval churches or spy agencies. For example in 1456, a clever code (still unsolved) was carved onto 215 ceiling cubes at Rosslyn Chapel (see www.youtube.com). English political agents had been using alphabetic codes for private correspondence since at least 1568, when Mary Queen of Scots was first put on trial for her “Casket Letters”. Those letters were translated into an alphabetic code by her secretary Gilbert Curle. Unfortunately her chosen courier for those letters was a double agent working for Queen Elizabeth! Everything Mary wrote was passed onto Elizabeth’s spies, and then onto a skilled codebreaker named Thomas Phelippes. He used a technique known as “frequency analysis” to break Mary’s secret code. First he looked for symbols used to denote the most commonly used letters of the English alphabet, namely “E” and “A”. Then he continued to find all of the less commonly used letters (see heritage.scotsman.com or tudorplace.com). Appendix 2. Could the binary code within “Head 20” provide us with medieval harp music as well as with a hidden text message? The binary code from “Head 20” was interpreted previously in terms of medieval harp music (see www.dailymail.co.uk). That is because certain musical scores of the era were written in a loose, unformatted binary notation (see www.pbm.com). Bill Taylor as an expert on medieval music commented: “The sequence of markings on that Head are similar to those used by medieval harp players in Wales. Yet if they are really musical notes, they don’t present any specific melody. Annoyingly there is nothing on the carving which supports a theory that the sequence must be musical” (see www.stirlingcastle.gov.uk). There may be some truth to the musical theory. Yet would medieval harp music show a well-formatted series of five-digit binary numbers, as we can see along the outer perimeter of “Head 20”? Such harp music may have just provided a convenient “cover text” for a deeper political message, which was then buried underneath. Appendix 3. Many words at the time of Francis Bacon were appended by an extra letter “E” From “Essays or Councils, Civil or Moral” by Francis Bacon: “Salomon saies a good name is as a precious ointment. And I assure my selfe, such will your grace’s name bee with posteritie. I doe now publish my essayes, which of all my other workes have beene most currant. For that as it seemes, they come home to men’s businesse and bosomes. I have enlarged them both in number and weight, so that they are indeed a new worke” (see www.gutenberg.org) |